Centre for Young Lives report warns poverty and hardship are preventing some children from attending school amid big increases in persistent and severe absence among children receiving Free School Meals

- Report shows how absence rates for the poorest children have grown fastest, with new analysis suggesting rates of persistent absence for FSM-eligible children since Covid have risen by more than double the percentage points of their peers.

- Report reveals troubling stories of children sharing shoes, missing school because they can’t afford PE kits, and insufficient identification of poverty as a driver for absence in the education system.

- Report reveals where children are severely absent and missing more than 50% of schooling, the rate has risen by more than three times more percentage points for FSM eligible pupils than non-eligible pupils.

- Report highlights how absence rates are much higher in some poorer areas than others. Children eligible for FSM in Bradford had over three times increased odds of becoming persistently absent at some point over their school career.

- Centre for Young Lives urges Government to scrap two child limit and expand FSMs to all children with families receiving Universal Credit; reduce the maximum number of school logos on school uniform from the proposed three to one; support schools to give families financial relief in times of crisis and include severe absence from school as a trigger for family support from children’s services.

[.download]Download the Report[.download]

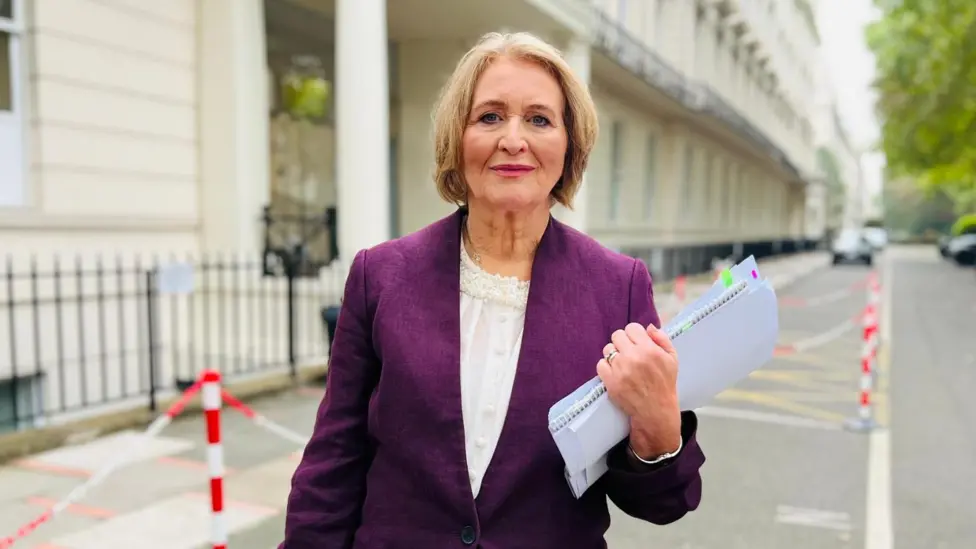

Anne Longfield, Executive Chair of the Centre for Young Lives think tank, is today (Tuesday December 3rd) publishing a new report, ‘Too Skint for School’, examining the link between poverty and school attendance.

The report warns that the costs of going to school is acting as a barrier to regular school attendance for some children from low-income families and urges the Government to break the link between poverty and school absence by boosting incomes of the poorest families, bringing down the cost of school, and improving identification and support for children and families coping with the impacts of poverty.

The report, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, includes analysis of DfE statistics by the Centre for Young Lives which shows children who are eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) are more than twice as likely to be absent than their peers across primary and secondary school – and that this does not even include the estimated 900,000 children who are growing up in poverty but not eligible for FSM.

The report also reveals how rates of persistent absence for FSM-eligible pupils since the Covid pandemic have risen by more than double the percentage points compared to the rise among those not eligible for FSM. Where children are severely absent and missing more than 50% of schooling, the rate has risen by more than three times more percentage points for FSM eligible pupils than non-eligible pupils.

The report also shows how some areas of high deprivation are seeing much worse attendance than other areas. A data deep dive into some schools in Bradford shows that over half (57%) of those identified as a persistent absentee in Bradford were eligible for Free School Meals. Children eligible for free school meals had over three times increased odds of becoming persistently absent at some point over their school career.

This analysis suggests that in recent years, school absences have been occurring earlier and earlier, at primary school age, and poor school readiness is becoming an indicator of absence downstream in school life.

The report argues that there is no clear, single story when it comes to the link between poverty and school attendance and there are multiple drivers of the current attendance crisis, including a disproportionate number of children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) who have found it difficult to get back into the routine of regular school attendance since Covid, or are not receiving the right support, many of those children struggling with anxiety and poor mental health, some children being affected by ‘Long Covid’, and a change in child and parent attitudes towards the expectation that children should be in school every day. However, poverty can exacerbate as well as create some of these challenges.

As part of its research, the Centre for Young Lives spoke with school leaders, attendance officers, youth workers, and some parents of school age children living on low incomes. These conversations revealed how some children are missing school primarily because of financial constraints and material deprivation, with uniform costs raised repeatedly as a concern for parents on low incomes.

Centre for Young Lives researchers heard much anecdotal evidence that the costs of attending school – particularly the costs of travel, uniform, and food – are more than some families can regularly afford. We spoke to parents on low incomes who were living a constant grind of managing the impact of having no money every day, draining their energy to battle with their children who didn’t want to go to school, for whatever reason.

We heard heartbreaking and troubling stories of children missing school because their family cannot afford the correct PE kit, or because parents can’t afford to pay bus or train fares to and from primary school twice a day, and even of two siblings who were sharing a pair of shoes and alternating days at school until teachers discovered what was happening.

The report warns that school identification of children where family deprivation is the leading factor behind their non-attendance is often uncoordinated and limited. While many schools are going above and beyond to support children growing up in poverty, others are not making allowances for deprivation as a driver to poor attendance, lateness, behaviour problems, or failing to comply with uniform rules.

The report makes a series of recommendations to Government to tackle some of the drivers of poverty and remove barriers which are in turn leading to some of the poorest children missing more school, including:

- Removing the two-child limit, introducing a protected minimum floor in Universal Credit, and expanding Free School Meals to all children with families in receipt of UC in the next school year, and to all primary school children by the end of this parliament.

- Reducing the maximum number of school logos on school uniform from the proposed three to one.

- Updating attendance guidance for schools to make it explicitly clear that poverty should be identified, considered and acted on in relation to school absence alongside encouraging schools to take a mindful approach to uniform in individual cases where it may be impacting school attendance.

- Supporting schools to give families financial relief in times of crisis as a key partner in the delivery of a permanent, reformed local system of emergency support.

- Including severe absence from school as a safeguarding and wellbeing risk factor, to trigger early family support from children’s services and ensure FSM eligibility and other demographic information is captured in the new Children Not in School register.

- Investing in an extended infrastructure of children centres and family hubs to provide integrated support to children and families, particularly in the early years and primary years, helping to prevent attendance problems before they become entrenched.

- Using Government’s primary school breakfast clubs roll out to introduce supervised toothbrushing in areas of high deprivation to reduce poor oral health among children which can lead to missed school for emergency dental appointments.

Anne Longfield, Executive Director of the Centre for Young Lives, said:

“Most children growing up in poverty regularly attend school. However, DfE data shows persistent absence and severe absence are both much higher amongst pupils eligible for free school meals. The new government’s ‘Opportunity Mission’ will be harder to deliver for as long as a significant number of children, some of them from the most deprived families, are missing school.

“I am very encouraged that school absence is now seen by the DfE as one of the big structural problems it faces – and that reducing school absence is recognised as an important factor in the government’s mission to reduce child poverty.

“The recommendations in this report have the potential to improve school attendance among children in poverty. That includes putting more money in the pockets of families and bringing down the cost of school. We also want to see stronger support for families, strategies from schools that recognise poverty, and better use of the DfE’s world-leading attendance data.

“A lack of money should never stop a child from attending school. We hope the government will heed our recommendations with urgency.”

ENDS

[.download]Download the Report[.download]

For more information contact: Jo Green jo.green@centreforyounglives.org or 07715105415.

Notes to editors:

- This report was funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and produced and published by the Centre for Young Lives.

- A copy of the report can be found here.

Meet the Authors

Meet the Author